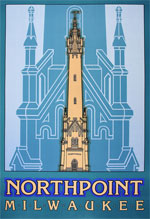

A picturesque water tower, a lighthouse, and a hospital – these are the North Point landmarks you see from across the bay. The view from within the neighborhood, below the treeline, is substantially different. North Point is a narrow band of gracious homes inlaid on the lake bluff like architectural gems. The fine homes and the sense of privacy have made North Point one of Milwaukee’s most desirable addresses for decades. But the neighborhood is also an integral part of the intensely urban East Side, and it lies barely two miles north of downtown. Its urban / suburban character and its prime location have given North Point a unique place in the city’s history, geography, and civic life.

Heritage

North Point’s history begins downtown. In the 1840s when Milwaukee’s social order was taking shape, the city’s leaders began to cluster on the high ground between the river and the lake, near the site of St. John’s Cathedral. There, within a stone’s throw of their shops and offices, prosperous businessmen and professionals built the most imposing homes of their time. As other neighborhoods filled in with immigrants, the high ground became a haven for Americans of British stock, most of whom had migrated from New York and New England. Their neighborhood was called, appropriately, Yankee Hill.

As Milwaukee grew, so did Yankee Hill. Fortunes were being made in milling, meat-packing, finance, railroads, and wholesale trade; architects were kept busy designing homes for the burgeoning elite. A second affluent district developed along Grand Avenue, west of downtown, but Yankee Hill was the older and larger of the two gold coasts. Year by year, the neighborhood expanded to the north and east, reaching the lake bluff in the 1860s and then edging up Prospect Avenue. By 1890 the avenue, with its magnificent “prospect” of the lake, boasted one of the finest assortments of Victorian mansions in the Midwest.

Speculators who held land in the North Point area had long sensed that a wave of affluence was heading in their direction. North Point South (between Lafayette Place and North Avenue) was subdivided and offered for sale as early as 1854. One prominent speculator, John Lockwood, built a lavish Italianate home on the site of Back Bay Park in 1856, presumably trying to start a trend. His instincts were correct, but his timing was unfortunate; it would take another forty years for the vanguard of wealth to reach North Point. Lockwood left town for other pursuits in 1863. His mansion, much abused after his departure, was demolished in the 1880s.

Speculators who held land in the North Point area had long sensed that a wave of affluence was heading in their direction. North Point South (between Lafayette Place and North Avenue) was subdivided and offered for sale as early as 1854. One prominent speculator, John Lockwood, built a lavish Italianate home on the site of Back Bay Park in 1856, presumably trying to start a trend. His instincts were correct, but his timing was unfortunate; it would take another forty years for the vanguard of wealth to reach North Point. Lockwood left town for other pursuits in 1863. His mansion, much abused after his departure, was demolished in the 1880s.

As speculators played their waiting game, development of another kind was well underway in North Point. The first known building in the neighborhood was, ironically, a poorhouse. In 1846, the year Milwaukee was chartered, the city bought a forty-acre tract to be used “for welfare or charitable” purposes. The tract was bordered by today’s Downer and Maryland Avenues between Bradford and North. The poorhouse (a hospital for the indigent) was erected in 1846, followed by a “pesthouse” for patients with infectious diseases. The Sisters of Charity moved up from downtown and opened St. Mary’s Hospital in 1858. A public school, Protestant and Catholic homes for the elderly, and an orphanage (now Lakeside Child and Family Center) were added later in the century. The poorhouse and pesthouse are long gone, but the other institutions are still on the original forty-acre site, giving North Point one of the densest clusters of health and social services in the county.

Public works projects also shaped the area’s appearance before homeowners arrived. In 1855 the North Point lighthouse was erected between two ravines on the lake bluff. Its beacon was a welcome sight for mariners at a time when lake traffic was absolutely essential to Milwaukee’s welfare. By 1879 erosion of the bluff was so extensive that the lighthouse had to be moved 100 feet west to its present location.

In 1871 construction of the city’s first water system began. A powerhouse on the beach below St. Mary’s Hospital pumped lake water up the bluff and under North Avenue to a huge reservoir just across the Milwaukee River. From there it flowed by gravity to the city’s homes and businesses. The Original pumps were as steady as a heartbeat, sending the water uphill in an endless series of surges. The constant fluctuation in pressure endangered the water main, and so engineers connected the main to a vertical pipe – 125 feet high and 4 feet wide – at the top of the bluff. The standpipe absorbed the surges and stabilized the flow of water to the reservoir. In a moment of inspired whimsy, City officials decided to enclose the pipe in a fanciful limestone tower. New pumps installed in 1908 made the standpipe obsolete, but the tower retains its fairy-tale quality.

The last public improvement of the nineteenth century was Lake Park. In 1890 the City park commission (then only a year old) purchased 120 acres on the lake bluff. The commission hired Frederick Law Olmsted’s firm to design a park on the site. (His other projects included Washington Park in Milwaukee and Central Park in New York.) Olmsted’s plans called for an elaborate system of carriageways, pedestrian promenades, and tree plantings that would divide the park into visually distinct sub-areas. Not all the plans were executed, but Lake Park became, and remains, one of the most artfully crafted links in a world-famous park system. The park movement’s leader, and the commission’s first president, was Christian Wahl, a retired glue manufacturer whose name lives on in the avenue that skirts the southern end of the park.

It was in the 1890s, when Lake Park was being developed, that the long-awaited residential boom finally reached North Point. As Prospect Avenue filled to capacity, well-to-do Milwaukeeans turned right at Lafayette Place and turned North Point into one of the most prestigious residential districts Milwaukee has ever known. Pabsts, Blatzes, Falks, Vogels, Brumders, and Smiths built homes that epitomized the latest and most luxurious in architectural trends. Some were simple, almost chaste, in their elegance, while others would have satisfied the appetite of any Eastern tycoon. All symbolized success.

Development continued over a forty-year period. North Point South was an established community by 1910, although some vacant lots remained until the 1920s. North Point North developed somewhat later. Its northern sections, aided by their proximity to Lake Park, filled in first. The homes on Newberry Boulevard (conceived as a link between Lake and Riverside Parks) are, on the average, older than those on Terrace Avenue to the south. By 1930, however, settlement in all sections was virtually complete.

North Point was different from earlier gold coasts in three important respects. It was, first of all, ethnically mixed. When Yankee Hill developed, Milwaukee was a commercial center whose leaders were, by and large, transplanted Easterners of British descent. By 1890 the city was a major industrial center, and scores of immigrants (and their sons) had become captains of industry. German, Irish, Czech, and other European families took their place alongside Yankees in North Point.

North Point was primarily a second-generation settlement. It was not the immigrants and Easterners themselves who built homes in the neighborhood, but their children, many of whom headed the family businesses. Villa Terrace, for instance, now a museum of the decorative arts, was built for industrialist AO. Smith’s son, Lloyd. His neighbors to the north were Gustave Pabst, Capt. Frederick Pabst’s son, and Elsie Cudahy Beck, Patrick Cudahy’s daughter.

The neighborhood was, thirdly, a metropolitan gold coast, especially after 1900. In the nineteenth century, practically every neighborhood had its own well-to-do sections. As horse-drawn carriages gave way to automobiles after 1900, affluent families were drawn to the lakefront. They moved from Grand Avenue on the West Side, from Walker’s Point on the South Side, from First Street on the North Side. A home near the lake bluff – in North Point or farther north – became Milwaukee’s ultimate status symbol.

The lake bluff itself was a problem as well as an attraction. The owners of homes fronting on the lake found their lots growing smaller every year as violent storms tore away at the bluff. The problem was solved in the 1920s, when the City began an ambitious landfill program. The project reversed the erosion process, and it gave all Milwaukeeans access to a stunning stretch of lakefront. Lincoln Memorial Drive, completed in 1929, became one of the most beautiful parkways on the Great Lakes.

In the 1920s, as North Point’s last vacant lots were filling in, a wave of transforming change began to move north from downtown. Milwaukee was growing rapidly, and its central business district was annexing the neighborhoods around it. Yankee Hill in its heyday was already a memory, and now the wave of change surged up Prospect Avenue. Dozens of mansions were torn down to make way for apartment buildings. Those that remained were converted to schools, offices, or rooming houses. The gold coast vanished.

The wave of change along Prospect and Downer Avenues bypassed North Point. A few apartment buildings went up, and a few mansions were divided into rental units, but the neighborhood retained its genteel residential character. The original homeowners typically stayed at least until their children were grown, and their children often bought homes nearby. Intermarriage was common – a Gallun to a Pritzlaff, a Friedmann to a Schuster -and the neighborhood was strengthened by family as well as geographic ties. Change would come, but North Point remained remarkably stable until well after World War II.

Home

In an important sense, North Point is its homes. What makes the neighborhood physically unique is the presence of so many homes of such quality in such a small area. There are nearly 400 houses in North Point. No two are identical, and all are substantial. Brick and stone are so common that frame houses are a rarity. Libraries, multiple fireplaces, and maid’s quarters are practically standard. North Point’s homes embody the taste of Milwaukee’s finest architects, the skill of the finest local craftsmen, and the material success of the neighborhood’s first residents.

In an important sense, North Point is its homes. What makes the neighborhood physically unique is the presence of so many homes of such quality in such a small area. There are nearly 400 houses in North Point. No two are identical, and all are substantial. Brick and stone are so common that frame houses are a rarity. Libraries, multiple fireplaces, and maid’s quarters are practically standard. North Point’s homes embody the taste of Milwaukee’s finest architects, the skill of the finest local craftsmen, and the material success of the neighborhood’s first residents.

Richard Perrin, former Commissioner of City Development and an accomplished architectural historian, summarized North Point’s architecture as “eclectic.” The neighborhood was developed as the Victorian era was ending and architects were reviving older styles, all with European roots. English Tudor homes are most numerous, but Georgian, Mediterranean, and German and French Renaissance styles are present as well. Architects adapted the traditions freely, producing distinctive homes that are often hard to pigeonhole in terms of style. Significantly, some of Milwaukee’s most prominent architects lived among their clients in North Point: the Alexander Eschweilers (Sr. and Jr.), Alfred Clas, Charles Crane, and Armin Frank.

There are numerous stand-outs in the neighborhood, including Villa Terrace at 2220 Terrace (as a museum, the only building open to the public), the Pabst and Goodrich homes to the north, the Nunnemacher mansion at 2409 Wahl, the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home at 2420 Terrace, the Trostel house and barn at 2611 Terrace, and the Gallun mansion at 3000 Newberry. But the overall level of quality is so high that the neighborhood is best seen on foot and with an authoritative guidebook.

Living

North Point seems to be, at first glance, a haven for the affluent: stately homes on tree-lined streets, abundant parkland, magnificent views of the lake, Audis and Volvos in the driveways. The North Point area’s housing values are the highest in the city, as are the income and educational levels of the residents. Perched above the lake, North Point is at a pinnacle, both physically and socially.

But the community’s social standing obscures the fact that it is a genuinely urban community. North Point is the east side of the East Side. Its residents overlook what is, in summer, the busiest expanse of parkland in Milwaukee. They look west and south to a high-density district of smaller homes and large apartment buildings. The St. Mary’s Hospital complex, at the heart of the neighborhood, brings hundreds of people into North Point every day. Two of the city’s most popular commercial districts – the “six points” cluster at Farwell and North, and the fashionable shops on Downer Avenue – lie on the neighborhood’s western border. North Point residents are among those who shop at Sendik’s, watch films at the Downer or the Oriental, dine at the Coffee Trader, drink at Von Trier’s, attend fish fries at the Italian Community Center, and borrow books from the East Library. Other East Siders, in turn (and residents of other neighborhoods), use North Point. Especially during the warm months, the blufftop parks are busy, and there is a steady stream of joggers, dog-walkers, and sightseers through the neighborhood.

North Point is part and parcel of the East Side, and its residents mirror the cosmopolitan diversity of the larger community. There are business people, professionals, professors, and cultural leaders. Political views run the gamut from very liberal to very conservative. There are retired couples, young singles, and families with pre-school children. Most of Milwaukee’s major ethnic and religious groups are well-represented. Three things unite this diverse assemblage: material success, an interest in historic preservation, and a taste for city life.

That taste was conspicuously absent twenty years ago. Although it survived long after similar districts had disappeared, North Point was, until recently, an endangered neighborhood. In the 1950s and ’60s, many of the old-line families moved out to newer homes in the North Shore suburbs, just as their ancestors had moved to North Point from Yankee Hill and other affluent districts. Some mansions were donated to religious or charitable groups. A few were bought and razed by Milwaukee County to create more parkland. Developers assembled blocks of houses and made plans for high-rise apartment buildings. As the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (established in 1956) drew more students every year, there was a growing demand for high density housing. Local institutions, particularly St. Mary’s Hospital, also began to acquire land for expansion. There was a widespread belief that North Point would become another Prospect Avenue. Housing values were depressed, and lenders required abnormally large down payments from the buyers of single-family homes.

A countercurrent was visible by 1970. The preservation movement was beginning, and there was a steadily growing interest in historic old homes. New residents arrived, including a sizable number from other states who were amazed at the quality and affordability of the area’s houses. The new owners joined a stable core of long-time residents and cemented a character that had been cracking. The neighborhood mounted a long campaign to ward off any and all threats to its low-density residential texture.

The effort was informal until 1973, when the Water Tower Landmark Trust was established. The Trust became one of the most unusual and most effective neighborhood organizations in the city. Its leaders worked for a new zoning ordinance and more rigorous building code enforcement. They negotiated with local institutions and developers. They spearheaded efforts to secure landmark status for the neighborhood. (Both sections of North Point were National Register historic districts by 1985.) They organized celebrations and open houses. Neighbors got to know each other through the Trust’s activities, and North Point became increasingly a community of interest.

Since the Water Tower Landmark Trust was formed in 1973, the trend has been steadily upward. All of the major threats have been deflected, if not eliminated. Housing values have soared. Numerous residents have moved back in from the suburbs, and there is a growing concentration of young families – an important sign for the neighborhood’s future. The population’s median age has declined steadily since the 1960s and, after an absence of decades, there are once again swingsets and jungle gyms in many backyards.

Fine homes, even finer views, and a prime location on the East Side – these are North Point’s enduring assets. The neighborhood’s residents are committed to preserving those assets for the next generation to enjoy.

Designed and published 1985 by the City of Milwaukee.